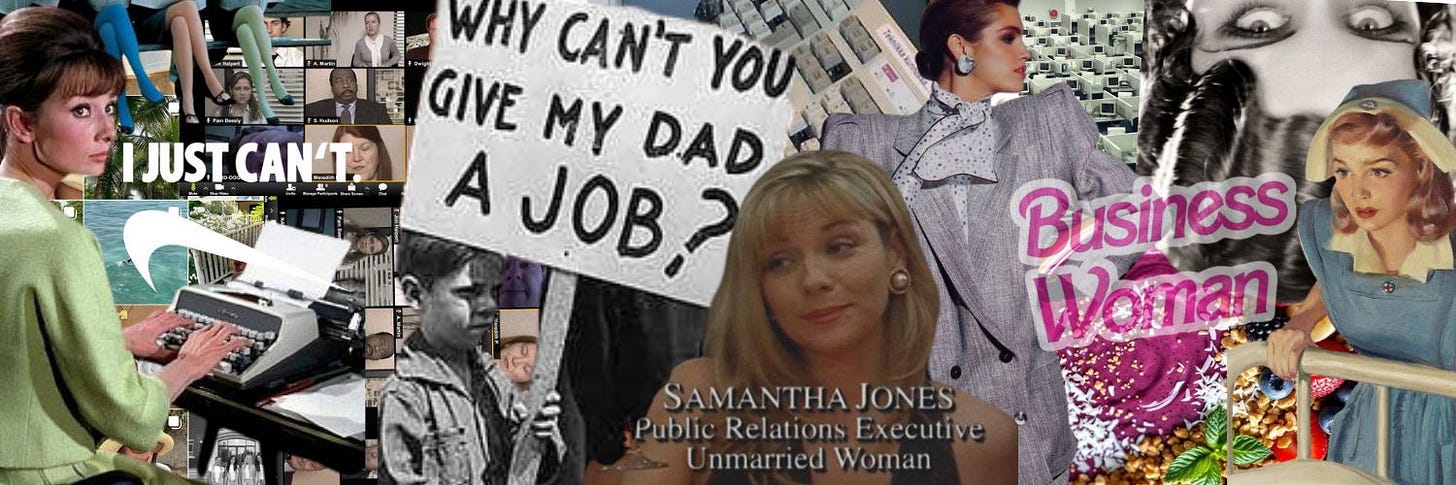

How to Succeed at Work (According to Dead Men)

100 years of career advice, straight from the boys club archives.

The corporate world loves to romanticise its own past. Mad Men, mahogany desks, mentoring sessions that are basically just golf and casual sexism.

Every few years, someone on LinkedIn rediscovers “deep work” or “being on time” like it’s a radical new idea.

What if we treated old career advice less like wisdom and more like evidence? Not all of it holds up under scrutiny. Some of it was built for a world that no longer exists – or never really did.

Some of the tips that got our grandparents promoted are still weirdly useful. But most only worked if you were a white man with a secretary, a salary, and zero interference from your nervous system.

I went digging. The results are equal parts brilliant and batshit. Occasionally both.

Let’s begin.

1920s – Proximity is Power

In the Roaring Twenties, proximity to power was everything. If you wanted to climb the ladder, you’d secure a seat near the boss, keep your ears open, and your ideas ready. Being seen by the right person sent a powerful psychological signal. By association, you were already part of the inner circle.

Now, proximity looks like replying to a Teams message within 40 seconds so they know you’re “there.” It looks like nodding on Zoom while your own face stares back at you like a hostage. It’s posting thought leadership on LinkedIn even though you haven’t had a real thought in months.

It’s bullshit. But it still moves the dial.

1930s – Suit Up

During the Great Depression, the logic was bleak – look richer than you are. Shine your shoes, starch your shirt, maybe throw on a fedora if you were feeling lucky. You might be broke, but at least you looked like you belonged somewhere better.

Almost a hundred years later, we’re still doing it. Not in three-piece suits – in boxy knits, good lighting, and the gnawing panic of looking employable from the collarbone up. Ambition doesn’t sit on your sleeve anymore – it lives in your lighting choices. Your pencilled-in eyebrows. The diploma you remembered to wedge into frame behind you.

1940s – Keeping Calm and Carrying On

Post-war offices were chaos. Men returned. Women stayed. Everything changed, and no one really knew what they were doing – so they made it up. People learned on the fly. Switched industries. Took roles they didn’t ask for. You either adapted, or you got left behind.

Not much has changed. These days, adaptability means figuring out Slack threads with 93 messages. Making decks for projects you don’t understand. Writing fake enthusiasm into emails about “the new system.” Calm is optional. Carrying on is expected.

1950s – Mind the Ceiling

In the 1950s, women reshaped the workplace. Long expected to just keep things afloat at home, they were doing far more – teaching in classrooms, caring for patients in hospitals, assembling the future on factory floors. The workplace wasn’t built for them, but that didn’t stop them from showing up, stepping in, and making shit happen.

Progress doesn’t just arrive. You push for it. You open the door and hold it – even when it’s heavy, even when no one says thanks. You name the bias when everyone else laughs it off. You back the intern. You call bullshit in meetings where everyone’s too polite to squirm.

You don’t have to be noble. Just don’t let the place slide backwards while everyone pretends it’s fine.

1960s – The Perfect Pitch

In the 60s, persuasion was everything. Ad men in grey suits chain-smoked their way through boardrooms, spinning half-truths into campaigns that changed culture. The pitch became the product – it didn’t matter what the idea was, as long as you could make people want it badly enough. It wasn’t just copywriting and charisma. It was knowing how to read a room, when to flatter, when to interrupt, and when to pretend you cared.

Fast forward to now, and we’re still pitching – only now it’s via slide decks, Slack threads, and half-hearted eye contact on video calls. You sell your ideas, your worth, your attention span.

Even though it feels a little soulless sometimes, clarity still cuts through. So does timing. So does being the one person in the meeting who actually knows what they’re talking about.

You’re not Don Draper. Doesn’t mean you can’t bluff like him.

1970s – Self-Help Takes Centre Stage

The 1970s, suddenly everyone had a notebook full of goals, a favourite productivity hack, and tools for figuring out how to lead without making everyone hate them. Self-help had officially arrived at work. Companies jumped on board, rolling out workshops on communication, time management, and goal-setting – turning the office into a personal development playground.

Alot of it was cheesy. But the 70s did get one thing right: no one’s coming to rescue your career. You either figure out what matters to you, or you end up stuck in a job that slowly erodes your will to rock up on Monday morning.

Learn something new, ask for help, stare into the void … whatever gets you through. Just don’t wait for your manager to hand you a development plan that actually means anything.

1980s – Fax to the Future

The 1980s gave us the fax machine – a hulking plastic beast that moved paper at what was, then, considered breakneck speed. Suddenly, you could send a document across the country without licking an envelope. Mastering the fax made you look tech-savvy, even if it jammed half the time and screamed like a demon being exorcised.

Today’s version of that isn’t a shiny new tool – it’s the expectation that you’ll learn every platform, automate your job, and streamline yourself into oblivion. You’re not just supposed to do the work. You’re supposed to optimise it, track it, and make it look effortless in Notion.

1990s – Mission Possible

In the ’90s, companies weren’t just selling products – they were selling purpose. Nike told you to Just Do It. Microsoft wanted a PC in every home. Mission statements became mandatory, plastered across mousepads, wedged into PowerPoints, and recited by managers who couldn’t remember your name. Purpose became part of the pitch – whether or not it meant anything.

Writing your own might feel daggy. Like something you'd be forced to do at a team offsite with beanbags, scented markers, and motivational quotes plastered around the room. Tbh … it does help to know what’s keeping you upright.

Jot it on a sticky note. Doesn’t have to be deep. Doesn’t have to impress anyone. Just something to stare at when you’re one email ping away from quitting your job.

2000s – When Work Went Global

The 2000s hit the workplace like a system update no one asked for. Jobs were outsourced. Entire departments vanished. Suddenly your biggest competition wasn’t the loud guy in sales – it was someone you’d never meet in a different time zone, working for half the cost. “Globalisation” sounded exciting in the brochures. In reality, it meant being told to do more with less while your boss bragged about cost efficiencies.

The subtext wasn’t subtle: adapt fast or risk getting cut.

If there’s anything worth salvaging, it’s this – build skills that feel like yours. Not just the tidy, marketable ones, but the messy, human parts too. The stuff that doesn’t fit in a dropdown menu.

If you don’t bring something only you can do, there’s a system that’ll do the rest.

2010s – Stay on Brand

In the 2010s, ‘being on brand’ was a new form of currency. Perfectly curated Instagram feeds, airbrushed influencer campaigns, and office outfits that said ‘girl boss’ became the norm. Everything you did had to reflect your carefully cultivated vibe. It wasn’t enough to do the work – you had to document it, hashtag it, and sell it with a smoothie in hand. Your vibe was your resume.

This level of curation is truly exhausting. What if you let your ‘brand’ get a little messy?

Maybe post something spontaneous, admit when you don’t have all the answers, or share a lesson you learned the hard way. There’s no need to perform relatability. Stop hiding the parts that don’t photograph well.

The Past Wasn’t A+

The workplace has always been a mess. Workplace history isn’t noble – it’s full of control, exclusion, and policies built for comfort, not fairness. We don’t need to romanticise it to admit that some things did work. Every era had its moments – even if they came with shoulder pads, chain-smoking, and a filing system that actively tried to injure you.

We’ve made progress, sure – but we’re still learning, still unlearning.

Take what works. Ditch what doesn’t. Please stop posting on LinkedIn like we came up with it all ourselves.

Another Slice?

33 Things I’ve Learned About Work in 33 Years

History offers perspective. So does ageing out of unpaid internships.